2020 will be remembered as one of the most challenging years in modern history, but at least we’re not facing a Thanksgiving meal without honey bees, at least not yet.

Honey bees and native pollinators are essential in our food system. One of every three bites of food – more than 100 agricultural crops raised in the United States – rely on insect pollination to produce fruit or seeds. Without the pollination services of our honey bees, also bumble bees, flies, butterflies and solitary bees, our grocery store shelves – and Thanksgiving table – would look mighty bare.

Pollination allows plants to set seed and to produce edible plant parts like fruit and nuts. Pollination takes place when honeybees visit flowers to collect nectar. In the process, pollen from the male part of that plant sticks to the bee’s furry body. When the bee visits another flower, some of the pollen rubs off, often on the stigma, the female reproductive organ of the plant.

Important stuff? You bet.

Some crops, like almonds, would be almost nil without pollination. The American Honey Federation estimates there are 2.7 million bee colonies in the United States, two-thirds of which travel around the country each year to pollinate crops. In California where 80 percent of the world’s almonds are grown, approximately 1.8 million colonies are required to adequately pollinate more than 1 million acres of almond orchards.

In fact, many of the commercial hives in Iowa right now are headed to California to provide pollination services for large horticultural enterprises and farms. Blueberries and cherries are 90 percent dependent on honey bee pollination. Other crops, such as potatoes, herbs, onions, garlic and carrots, need pollination to be able to produce seeds for the next year’s crop. Many crops simply yield more with better pollination.

The cornucopia image above shows only some of the foods that would be missing (the sweet corn and oats would be safe because they are wind-pollinated).

So let’s look at a typical Thanksgiving meal. You would not recognize it if we had no pollinators.

- You would still have the star of the meal, turkey and dressing, but forget about adding those things that give this dish its flavor including onions, garlic, sage and thyme.

- Green bean casserole? That’s a go because green beans, lima beans and peas are self-pollinated. But stray beyond the standard fare and you’re in trouble. No squash or broccoli-cauliflower casserole, and you wouldn’t be able to have another popular choice, brussels sprouts.

- Potatoes and gravy? Only the gravy.

- Corn? No problem. But sweet potatoes, no way.

- How about the relish tray? No carrots, celery, radishes or cucumbers.

- You would have wheat to make rolls and the dressing, whether it’s made with bread or cornbread, but no honey to put on the rolls. And forget about jams – cherries, plums, gooseberries and currents are out.

- No cranberry sauce for the turkey, and you could not even substitute horseradish.

- The finishing touch? No pumpkin pie or apple pie!

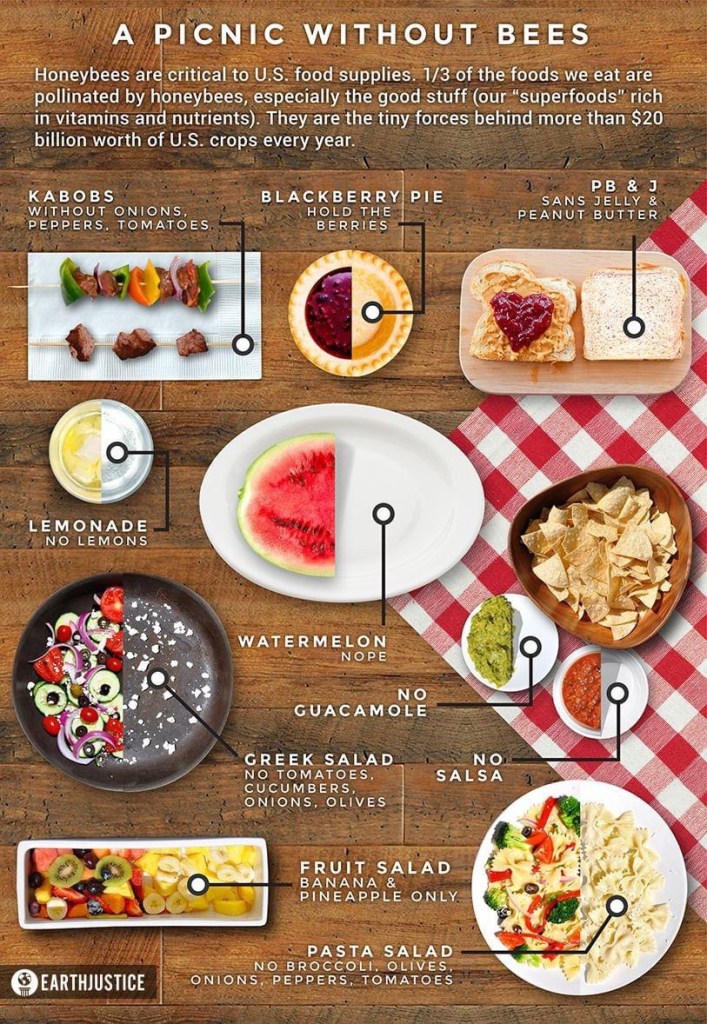

A lot would change without our pollinators. I was inspired to check out a Thanksgiving without bees after I saw “A Picnic without Bees” image below from Earth Justice, an environmental law organization based in San Francisco. Other organizations have created similar illustrations designed to help us envision a world without pollinators.

I really like Susan Slade’s children’s book, “What If There Were No Bees?” (2011 Picture Window Books). She delightfully shows a grassland ecosystem with and without bees. There are flower gardens, crop fields but also the insect-animal food chain that’s broken when there are no bees.

“Grassland ecosystems can be found on nearly every continent,” she writes. “Countless animals and plants live in them. So what difference could the loss of one animal species make? Follow the chain reaction and discover how important bees are.”

It’s an interesting picture but not one I want to face anytime soon. That’s why I’ve put honeybees on the top of my gratitude list for Thanksgiving. I hope you will, too!

Here is another interesting look: